- Blog

- Speed you can trust: The STT metrics that matter f...

Feb 13, 2026 | Read time 7 min

Speed you can trust: The STT metrics that matter for voice agents

What “fast” actually means for voice agents — and why Pipecat’s TTFS + semantic accuracy is the clearest benchmark we’ve seen.

TL;DR

There are lots of latencies in transcription, but for voice agents the time from finishing speaking to a final transcript is the most important.

Pipecat have released possibly the best benchmark for voice agent transcription testing the correct latency and ‘Semantic’ accuracy.

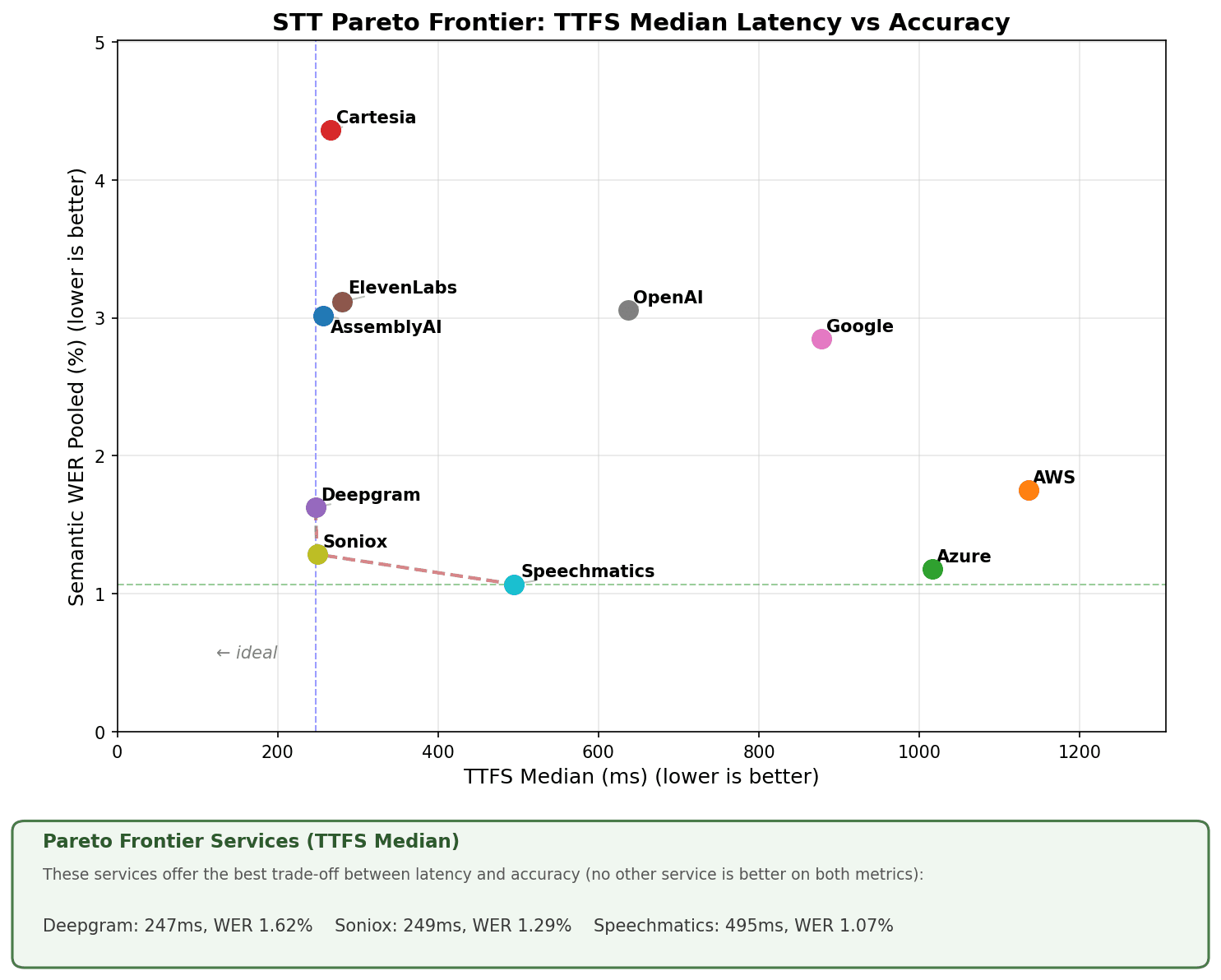

We are the highest accuracy provider and deliver finals in 495ms according to their testing.

For voice agents, latency only matters once a transcript is accurate and stable enough to act on. This post breaks down which speech-to-text timing metrics actually affect agent response speed, and why Pipecat’s evals are the clearest signal we’ve seen so far.

In transcription, there are lots of acronyms for lots of latencies, but, only one that truly counts for voice agents.

It’s hard to benchmark real-time latency and accuracy.

There are only a handful of public benchmarks, such as Coval.ai, before you have to resort to metrics from STT providers which always seem to end up… favorable, shall we say.

We have our own internal metrics of course, which we think are robust and fair - but why would you trust us?

The most important thing to remember? Any latency metric needs the context of accuracy.

I would rather talk to a bot that takes 100ms longer to respond but not have to repeat myself because it transcribed something wrong.

And not just accuracy: reliability and cost have to factor in when making a decision about a provider.

That's why we aren't just targeting speed - we’re targeting “Speed you can trust”.

In this post I will run you through what the real latency of a voice agent is, the various transcription ‘speeds’ I see talked about in the market and which count for voice agents. I’ll then give you a rundown of the Pipecat evaluations and why I like them so much.

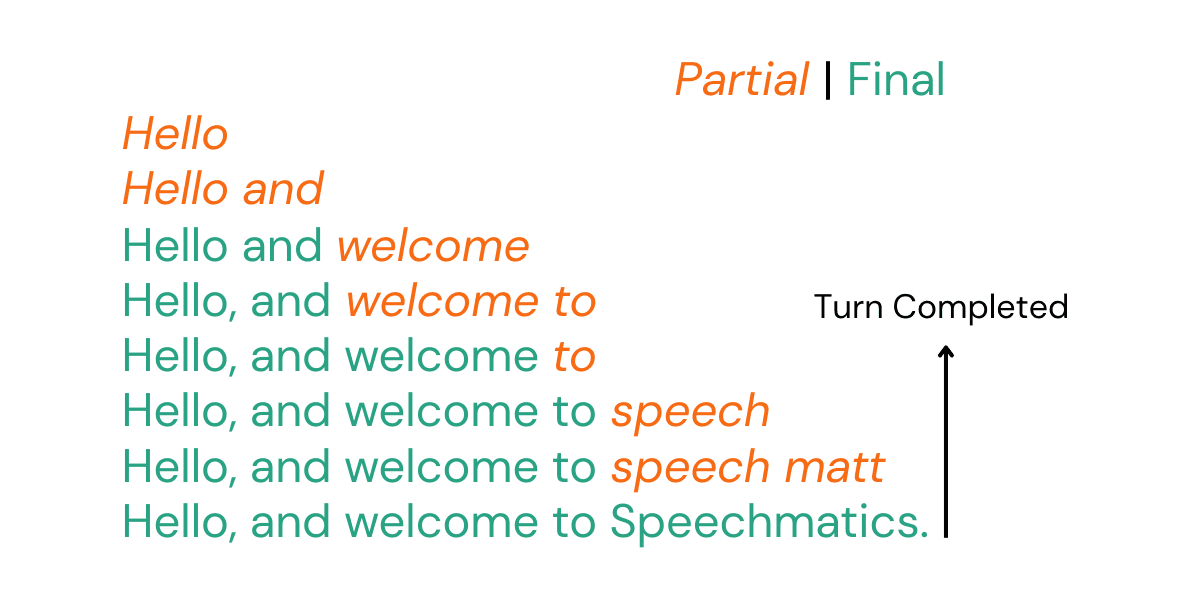

Partials, finals and turns?

Just to catch everyone up on the lingo:

Partials

Partial transcripts, sometimes called ‘interim’, are the current best guess.

They are a volatile transcript subject to change.

If you are halfway through a word ‘Speech matt’ it will output its current best guess and update it as you finish speaking or as context around it changes. These are ultralow latency being emitted sometimes before you even finish a word.

Mostly you would just use them as a visualization, and confirmation of the transcription process. But some people do use them for ‘speculative generation’ - going to the LLM before the user finishes speaking.

Finals

A final transcript is, well, final.

Once emitted, we won't change it.

Because we won't change it, we fundamentally need a longer amount of time between you saying a word and us giving it back to you as a final.

We need to make sure that you are not halfway through a word, or that the surrounding context doesn’t change what we think you have said.

These make up the ground truth that is generally used to go to the LLM.

Turns

A turn is one half of a conversation. My turn is finished when I stop speaking and expect a response.

The challenge for any system is knowing the difference between a mid-sentence breath and a finished thought.

If I say, "Add to the shopping list, a box of whatsitcalled… " and stop, I'm likely just searching for a word.

If I say, "Add to the shopping list, a box of Earl Grey tea" and then stop for 500ms, the turn is likely complete and the agent should respond.

Detecting this boundary in real-time is a specific engineering problem.

Frameworks like Pipecat and LiveKit use their own turn-detection models to decide when to "close" the user's turn and trigger the LLM.

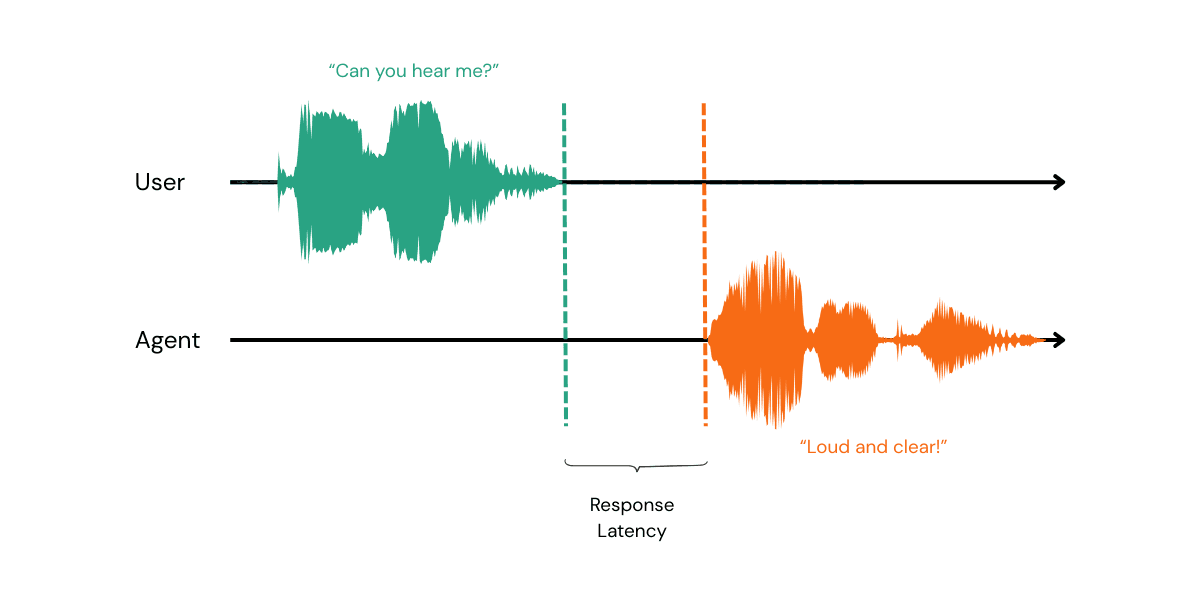

Voice Agent latency

Also sometimes called speech-to-speech latency.

When people talk about latency of a voice agent they mean the response latency; the time from me finishing speaking to the bot starting speaking.

In that time a lot of things have to happen.

The first of which being detecting the person has actually finished speaking and getting the final transcript back from the transcription service. Then someone else can do the rest: RAG, LLM call streaming the output to a TTS service which in turn is streaming audio back to the user.

Transcription Latencies, and what contributes to voice agent latency

If you really want to get into it, you can slice and dice latency any which way you like.

Here is a subsection of the numbers I see most often, ordered from "least relevant" to "most critical" for voice agents:

Metric | What it actually measures | Relevance to Voice Agents |

|---|---|---|

RTF (Real-Time Factor) | Speed of processing vs. audio length. | Basically None. Is really a metric for pre-recorded audio. For real-time you just need it quicker than 1. |

TTFB / TTFT | Time from audio start to first piece of text. | Low. A vanity metric. Easy to game by firing back wrong words early. |

Partial Latency | Delay from a word finishing to a volatile guess. | Medium. Good for "perceived" speed and speculative LLM prompts. |

Finals Latency | Delay from a word finishing to a stable, fixed transcript. | Medium. Similar to partials - good for GUI if you have one or speculative generation |

TTFS (Time to Final Segment) | Time from user finishing speech to receiving the final segment/transcript. | High. This is the ‘transcription latency’ people mean when talking about voice agents |

Response Latency | Time from user finishing speech to voice agent responding | High. Includes Transcription, LLM and TTS. This is the latency of a voice agent, and massively affects the user experience. |

RTF (Real-Time Factor)

First off, this is not a latency. This is what you might call ‘speed’.

It's not really relevant to real-time applications at least from a user perspective. But it is a number that shows up a lot on batch benchmark sites.

This is how long it takes to transcribe a second of audio (on average). So if you send us a 100 second audio file and we process it and give the transcript back to you in 5 seconds we would have an RTF of 0.05. Lower is better.

As I say this has very little to do with the user experience of real-time transcription and voice agents latency.

As long as this is less than 1 (i.e. real time) all is good. Artificial Analysis measure what they call a Speed factor for a 10 minute section of audio. Speed factor is the reciprocal of RTF (higher is better). They measure a Speed Factor of 43.9 for our standard and 24.1 for our Enhanced models. Although this will vary by file size.

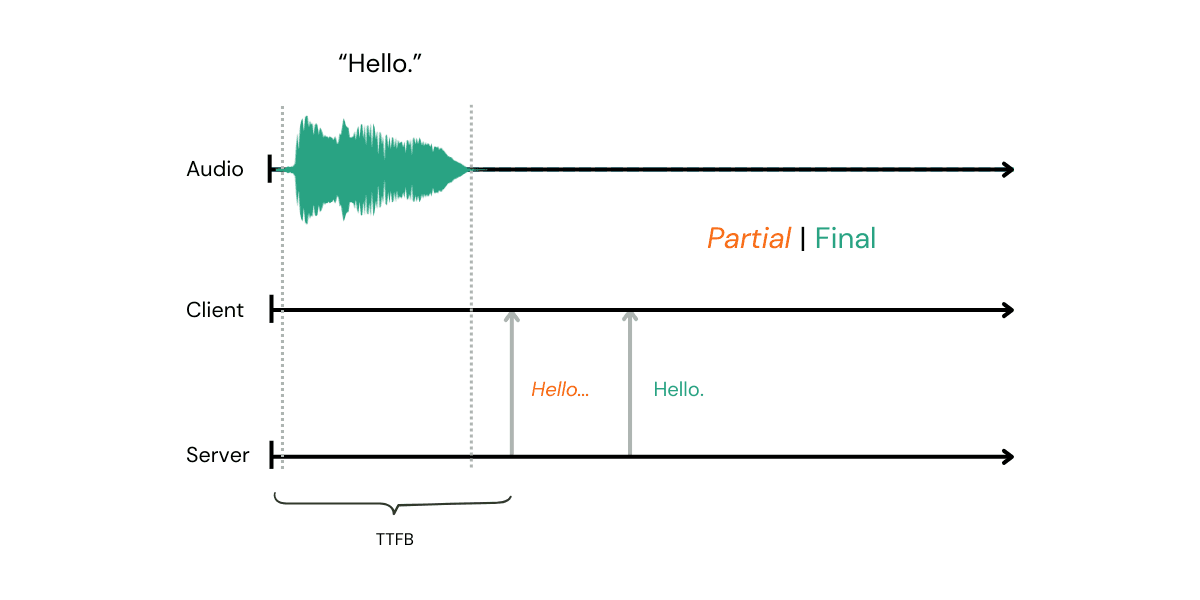

TTFB (Time To First Byte)

Sometimes known as TTFT (Time to First Token/Transcript). In my opinion, this is the worst metric in the industry, but I see it cited over and over again.

This is the delay from the moment you start streaming audio to the moment you get the very first piece of transcript back.

There are a few things wrong with this. Primarily: how long is a word? If I say "Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious," an STT engine is well within its rights to wait until I’ve finished the mouthful to ensure the transcript is accurate. That results in a "long" TTFB. Alternatively, an engine could fire back "Super" almost straight away. On paper, that's "faster," but it hasn't given the agent any useful context yet.

Returning a fragment early isn't necessarily a bad thing, but consider the case of Deepgram Flux as reported by the benchmarks at Coval.ai.

If you look at the data, they almost always return the word "Two" first, regardless of what is actually being said. It’s likely just a statistical bias toward common first words in a dataset. They return it incredibly quickly but it’s not meaningful. Firing back a volatile guess doesn't make a service fast.

It just means the rest of your AI stack has to wait for a correction anyway before it can actually do anything.

STT ≠ TTS (or LLMs)

TTFB is popular because it’s a standard way to measure LLMs and TTS systems.

It's like there is a natural parity between the stacks, but that is silly. The best argument for it is that it's a proxy for the rest of the latency picture, but that is also silly. It's just easy to measure. You send in some audio and see how long it takes for something - anything - to come back. In transcription, the first byte is often just a guess that might change a millisecond later. It’s not a reliable indicator of when your agent can actually start working.

Head over to the STT benchmarks at Coval, to find independent TTFB measurements, but pay attention to our WER and what others send back in their first byte.

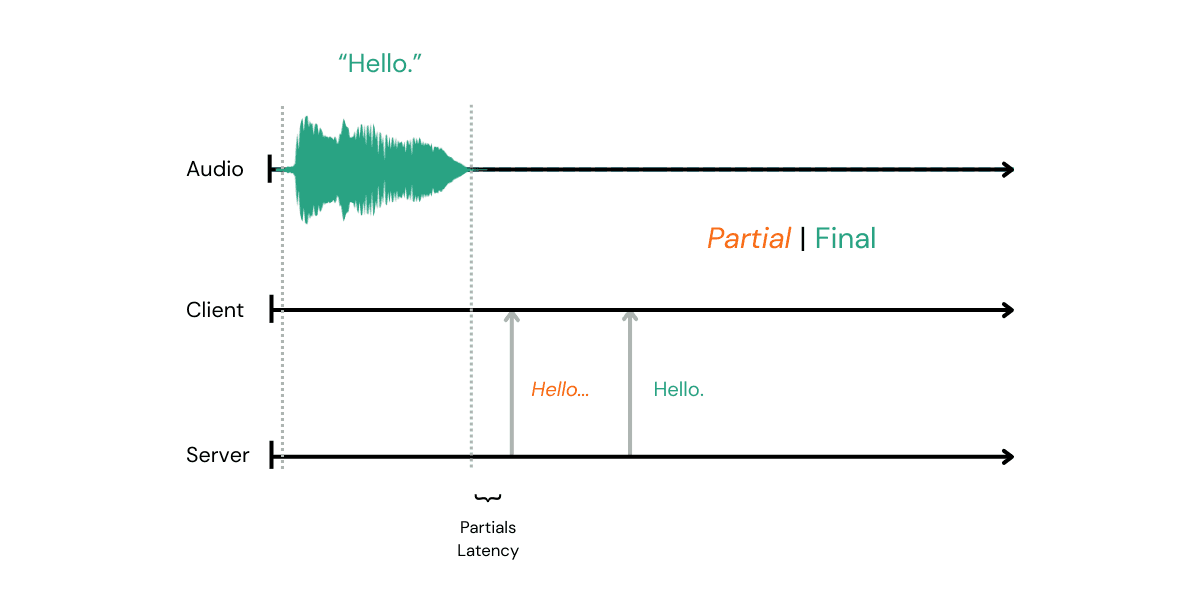

Partials Latency

This is sometimes called ‘word emission latency’.

I’m talking about the time from me finishing a word to getting the first partial that relates to it. Note that the partial could be right or it could be wrong. As with all these latencies, there is an accuracy associated with all of them.

It's also worth noting Partial Update Cadence - this is the rate at which Partials are changed after they first arrive.

Partial latency is probably what a lot of people ‘feel’ when using a transcription service with written output. Even if it’s a partial and sometimes wrong or halfway through a word, the partials give you real-time feedback as you talk. Generally, the quicker that happens, the happier the user is.

For voice agents, partials could potentially be used for speculative generation. You go to the LLM ahead of me finishing a turn so that as soon as I finish speaking, you are ready to go.

Similarly, you could use the partials to do semantic turn detection - does this sentence look like it's finished?

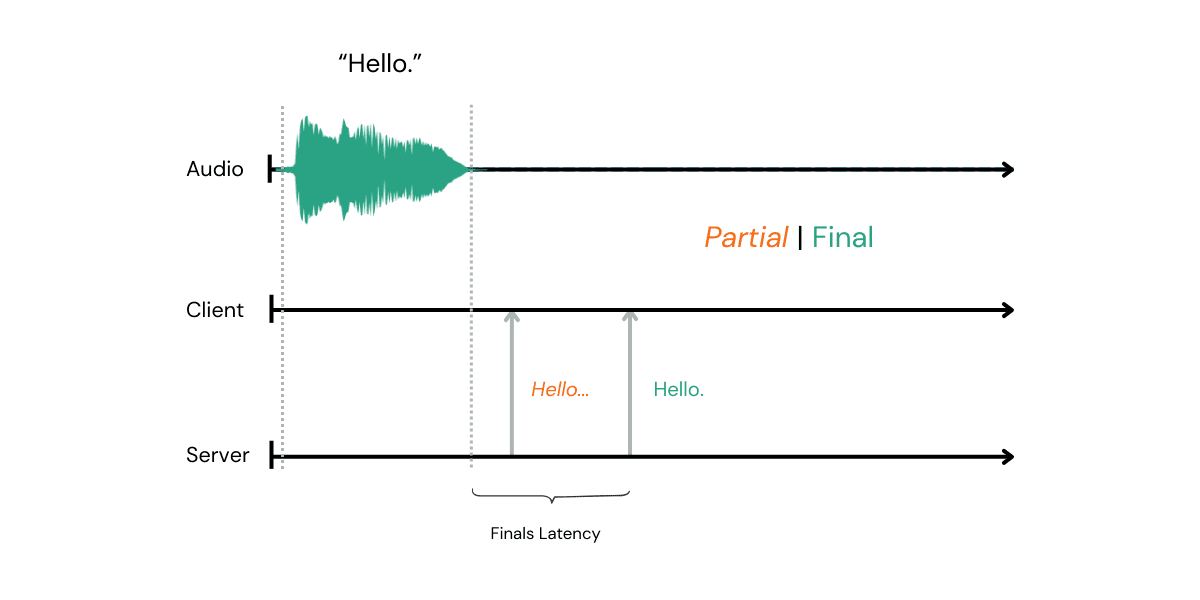

Finals Latency

Similar to partial emission latency, this is the time from the word finishing to the relevant final coming in.

We give you fine grain control of this with our max_delay setting in the API.

It sets how long after a word the system is allowed to wait before it has to call it a day and give you a final. Because we value accuracy the lowest we currently let you go is 700ms. Beyond that we started to see a degradation in accuracy that we just didn’t feel comfortable with. That is not to say we can’t give you finals faster than that as I will get to. This matters for receiving finals as you are speaking and updating the running transcript, for instance for live captioning this is the latency that counts.

For voice agents we recommend a max_delay of around 1.5s giving a balance of accuracy and delay. Which is not to say we can’t deliver final transcripts faster than that once you are done speaking. Which leads me to…

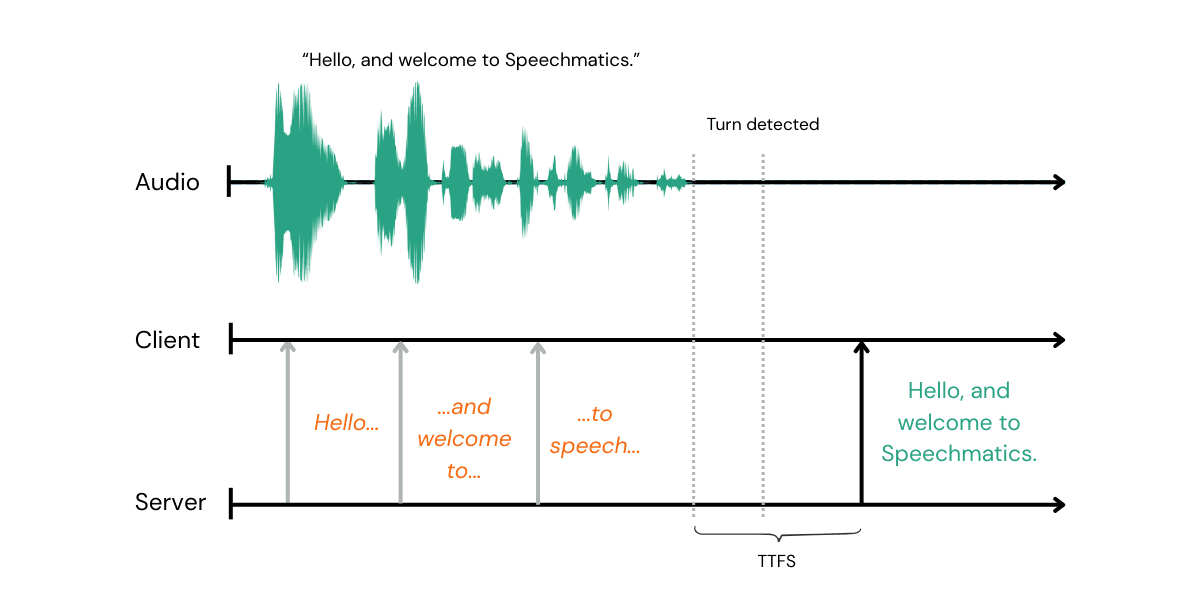

End-of-Speech to finals latency

This is the transcription providers share of the 'voice agent latency'. The time from when I finish speaking to getting back the final transcript that is passed off to the LLM.

For a transcription service, the important thing is getting the final back as quickly as possible - given, that I have in fact finished speaking.

I will be calling this End-of-speech to finals latency but you may hear it called EoT latency (although we think that should be reserved for how long before you detect the turn is over).

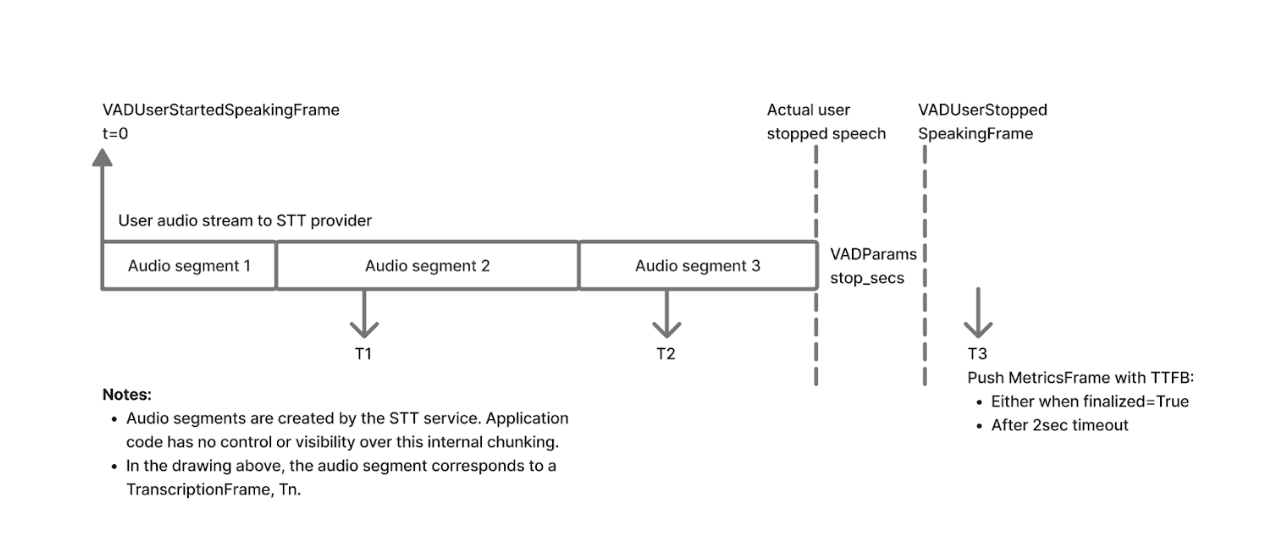

Pipecat is calling it TTFS (time to final segment) publicly but TTFB (time to first byte) in their code. Helpful.

In short, currently our system lets someone else (Pipecat, Livekit etc) detect a turn in ~200ms, they tell us to finalize (with a force_end_of_utterance message) and then we send back a final transcript in 250ms.

You can read more about this in my very first blog post.

Our internal tool detects an end-of-speech to finals latency of 0.451 ± 0.022s for our new Voice SDK which has turn detection built in.

But we think the best benchmark is from Pipecat.

Pipecat evals: Best voice agent benchmark?

Service | Transcripts | Perfect | WER Mean | Pooled WER | TTFS Median | TTFS P95 | TTFS P99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Assemblyai | 99.8% | 66.8% | 3.49% | 3.02% | 256ms | 362ms | 417ms |

Aws | 100.0% | 77.4% | 1.68% | 1.75% | 1136ms | 1527ms | 1897ms |

Azure | 100.0% | 82.9% | 1.21% | 1.18% | 1016ms | 1345ms | 1791ms |

Cartesia | 99.9% | 60.5% | 3.92% | 4.36% | 266ms | 364ms | 898ms |

Deepgram | 99.8% | 76.5% | 1.71% | 1.62% | 247ms | 298ms | 326ms |

Elevenlabs | 99.7% | 81.3% | 3.16% | 3.12% | 281ms | 348ms | 407ms |

100.0% | 69.0% | 2.84% | 2.85% | 878ms | 1155ms | 1570ms | |

OpenAI | 99.3% | 75.9% | 3.24% | 3.06% | 637ms | 965ms | 1655ms |

Soniox | 99.8% | 84.1% | 1.25% | 1.29% | 249ms | 281ms | 310ms |

Speechmatics | 99.7% | 83.2% | 1.40% | 1.07% | 495ms | 676ms | 736ms |

Note the two axes: semantic word error rate (WER) and median TTFS (Time to first segment).

To create this they use their own data set created originally to train their turn detection model Smart Turn V3.

It’s a set of small utterances, some cut off and some finishing naturally, as an end of turn.

This semantic WER is an attempt to capture accuracy as it means for a voice agent.

Can the LLM understand what you mean based on what was transcribed? How do they decide this? You ask an LLM to do it for you.

They pass the audio through Google’s transcription service to get a ground truth (this is questionable - why them and not anyone else? But can be human corrected). Then they have a huge custom prompt they have created, which essentially asks Claude to check if the meaning of a transcription matches the Google ground truth and divides this up into an error per word.

The TTFS is really exciting for me personally as this is exactly what I have been trying to do - in a hacky job - over the top of vanilla Pipecat for a while now.

Within Pipecat's turn detection system there are two models, Silero VAD (voice activity detection - is someone speaking right now) and their Smart Turn V3 model.

They work in conjunction. Once the VAD goes low for stop_secs, then the Smart Turn model is run on the audio and decides if the user is done speaking. Then, for Speechmatics, they send a message to us to say the user is done speaking and we should finalize.

The TTFS time is then the time from the VAD initially going low to the finals coming back. This is a good way of measuring end-of-speech to finals latency. Internally we use the exact timing of the final word to measure this (as determined by something called ‘force alignment’), but this is complicated and using VAD in this way makes it scalable to every user.

"Speed you can trust"

Just a little bit then on why we are happy where we sit on the Pipecat chart.

Speed you can trust.

Obviously a little bit of marketing fluff, but I am proud to say I did come up with it myself.

And fluff or not, the point is valid.

Speed is important - but accuracy is really important.

We will keep pushing down our latency for voice agents but not at the cost of lowering our accuracy. If it's a trade between waiting 100ms extra vs your users having to repeat themselves; we are taking the 100ms every time.

So we are very happy being most accurate on the board, with 83.2% of our Pipecat's tests being completely perfect. This evaluation also shows off the work we have been doing to push down our latency that is available now in our Pipecat integration.

Something I also want to point out is that the Pipecat evaluation here only uses English on a particular test set, but accuracy is much broader than that. Accuracy can be measured: across languages, specific domains (we are really good at medical) and accents. And our latency is consistent across all of them.

P.S. If you are looking for value, our Standard model is cheaper and more accurate than Deepgram, with the same improved latency as our enhanced model.

Try it yourself

I have updated the Pipecat example on the Speechmatics academy to the latest release (Pipecat 0.101) which now has the TTFS measurement for transcription services.

To test us out:

clone the repo https://github.com/speechmatics/speechmatics-academy/tree/main/integrations/pipecat/02-simple-voice-bot-web

grab your your free API key from Speechmatics,

spin up the bot.

Make sure you use the closest endpoint to you for the lowest latency; we default to EU.

As you talk to the bot normally, the metrics tab in the web UI should update to show the live TTFS for each turn.

Conclusion

It's exciting times for voice agents, and Pipecat has delivered the most comprehensive benchmark for them so far.

But as much as I think about latency (and believe me, it occupies most of my waking thoughts...) I keep coming back to the same conclusion: accuracy matters more.

Latency has reached a point where you can have a comfortable conversation with a voice agent.

People who say 'latency is UX' aren't wrong, but repeating yourself because the system mishears you is far more annoying than waiting an extra 100ms.

Right now, the transcription latency for voice agents is from finishing speech to getting finals back.

But who knows if that will be the case in a year (speculative generation anyone?).

I think turn detection will become layered between transcription, orchestration and the LLM; all adding backstops for turn detection. We'll see more and more of the turn detection being baked into the transcription services (watch this space), pulling on more information; the synthesis of auditory and textual information and potentially both sides of the conversation.

Fast matters.

Fast, reliable and accurate across languages, accents, and domains matters more. Well that’s speed you can trust ;)

Appendix

A note on algorithmic latency.

All the pretty pictures I made above assume the speed of light is infinite. It isn’t.

Network latency is relevant to all client side latencies. But for us measuring latency we are talking about the so called ‘algorithmic latency’ which is what you would get if you sat with your laptop plugged into our servers. The Pipecat evaluations do however include real world network latency.

Related Articles

- TechnicalJan 21, 2026

You can’t hurry love, but you can hurry final transcripts

Archie McMullanSpeechmatics Graduate - Use CasesFeb 3, 2026

7 Voice AI predictions from teams building at scale in 2026

Maria AnastasiouEvents & Customer Marketing Lead - CompanyJun 10, 2025

The scaling challenge voice AI can’t ignore

Owen O'LoanDirector of Engineering Operations

Latest Articles

![[alt: Bilingual medical model featuring terms related to various health conditions and medications in Arabic and English. Key terms include "Chronic kidney disease," "Heart attack," "Diabetes," and "Insulin," among others, displayed in an organized layout.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F3I31FQHBheddd0CibURFBv%2F4355036ed3d14b4e1accb3fe39ecd886%2FArabic-English-blog-Jade-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Speechmatics achieves a world first in bilingual Voice AI with new Arabic–English model

Sets a new accuracy bar for real-world code-switching: 35% fewer errors than the closest competitor.

![[alt: Illuminated ancient mud-brick structures stand against a dusk sky, showcasing architectural details and textures. Palm trees are in the foreground, adding to the setting's ambiance. Visually captures a historic site in twilight.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F2qdoWdIOsIygVY0cwl8UD4%2Fe7725d963a96f84c87d614ccc6cce3c6%2FAdobeStock_669627191-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Your voice agent speaks perfect Arabic. That's the problem.

Most voice AI models are trained on formal Arabic, but real conversations across the Middle East mix dialects and English in ways those systems aren’t built to handle.

How Nvidia Dominates the HuggingFace Leaderboards in This Key Metric

Why predicting durations as well as tokens allows transducer models to skip frames and achieve up to 2.82X faster inference.

![[alt: Healthcare professionals in scrubs and lab coats walk briskly down a hospital corridor. A nurse uses a tablet while others carry patient charts and attend to a gurney. The setting conveys a busy, clinical environment focused on patient care.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F3TUGqo1FcOmT91WhT3fgbo%2F9a07c229c11f8cbe62e6e40a1f8682c7%2FImage_fx__8__1-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Why AI-native EHR platforms will treat speech as core infrastructure in 2026

As clinical workflows become automated and AI-driven, real-time speech is shifting from a transcription feature to the foundational intelligence layer inside modern EHR systems.

![[alt: Logos of Speechmatics and Edvak are displayed side by side, interconnected by a stylized x symbol. The background features soft, wavy lines in light blue, creating a modern and tech-focused aesthetic.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F7LI5VH9yspI5pKWFeiZBXC%2F92f6a47a06ab6a97fb7f5a953b998737%2FCyan-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

One word changes everything: Speechmatics and Edvak EHR partner to make voice AI safe for clinical automation at scale

Turning real-time clinical speech into trusted, EHR-native automation.